Concept Mapping

Concept maps are graphical tools for organizing and representing knowledge. They originated during the 1960s when scientists were trying to understand how infants learned, and there wasn’t a tool available to map out the complex, interconnected processes. It turns out concept mapping is a useful learning tool, both in creating them and sharing one’s understanding. This article presents essential detail about what knowledge is, how we develop it, and how we represent it in concept maps.

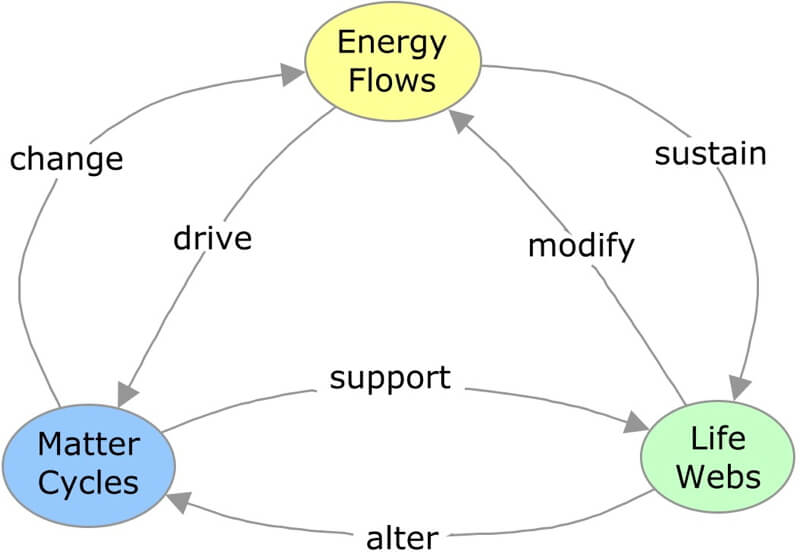

In essence, a concept map involves creating a network of nouns connected by action verbs. Above is a high-level concept map of Earth Systems Science. The arrows on the lines show what is acting on what.

A concept map of the three fundamental components of Earth systems.

Creating a Concept Map in a Nutshell

The first step in creating a concept map is to identify the nouns associated with the topic. ‘Creating a parking lot’ is the process of listing the important nouns in one place (the parking lot). And just as in a parking lot, the types of cars are not well organized throughout the lot. Key is to get them in one place first. Once you have identified the important concepts, spatially organize them based on their influence on and relationship with each other. Next, add the direction of the connection and describe the action of the connection using an effective verb. This is the most challenging part of creating a concept map since it requires a deep understanding of the connection to create clear, informative linking verbs. Most likely the first draft of the concept map will be quite challenging for anyone else to understand. Keep improving the clarity and organization of the concepts and links as you continually ask yourself “Is this what I mean to say?”

Tips When Creating Concept Maps

- Try to minimize crossing links.

- Avoid ‘danglers’ – concepts not connected to anything else following it. Danglers usually are not critical concepts.

- Use action verbs that describe the connection between the two concepts. ‘Is’ and ‘has’ are poor descriptive verbs.

Make Your Concept Map

Step 1: Create a parking lot of one of your favorite activities (hobby, sport, something you find gratifying). Try to create a thorough list of the nouns associated with the action. Use a pencil and paper, whiteboard, chalkboard, notecards, scraps of paper, or Post-Its.

Step 2: Cluster your nouns into groups that have a common theme or relationship. Most likely, when you create your concept map, these will be close to each other to help minimize crisscrossing links. If you used notecards/scraps/Post-Its, this makes it easier to move the concepts around.

In a sense, you could call this the parking garage step – you are creating levels to organize the “cars.” Identify the big or over-arching themes and arrange these relative to each other.

In the following example, first, arrange the nine major reservoirs of Earth’s water cycle before creating the concept map.

- The atmosphere needed to be in the center since it connects with the other reservoirs.

- The ocean is the predominant reservoir of water on the planet, so it is located halfway between the top and the bottom.

- The reservoirs where water flows into and out of are at the top.

- The remaining reservoirs are in the lower half of the concept map.

Spatially organize the main concepts for the water cycle before adding the connecting links and verbs.

Step 3: Download CMAP Tools, which is free and works on Macs and PCs. There is a web-based version that will work on Chromebooks and a version for iPads.

Step 4: Create a concept map of your favorite activity. There are tutorials available. Display CMAP’s Style Palette to modify colors, boxes, lines, fonts, etc. Go to Window in the File Menu and then click ‘Show Style Palette’.

Step 5: Share your concept map with someone and have them look at it for several minutes without talking. Then, discuss your activity. Are you surprised how well they understand why you like your activity?

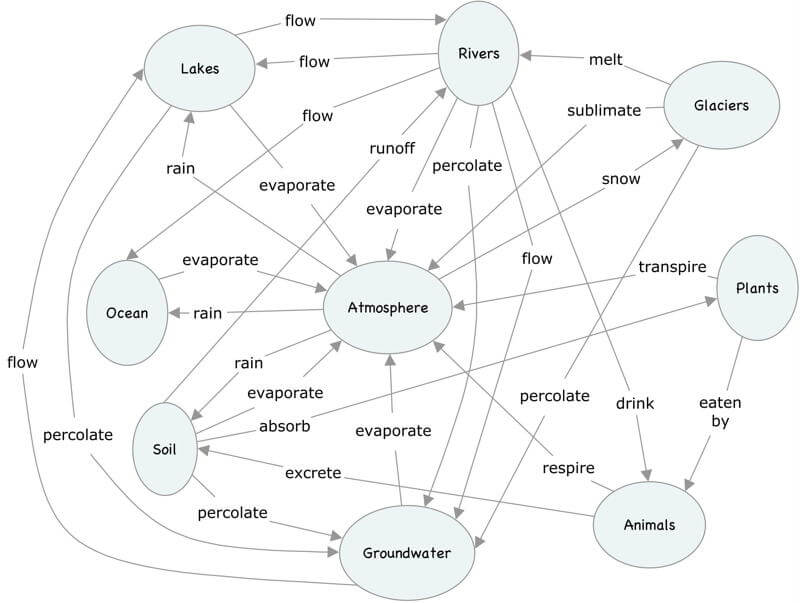

A completed concept map of the water cycle.

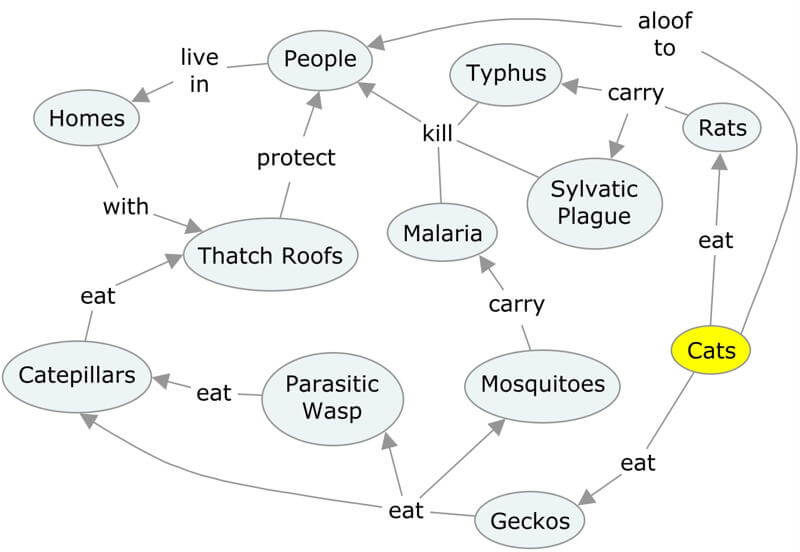

Step 6: Interpreting Concept Maps. Above is an example of a rather complex concept map of a village of people living in Borneo in the 1950s. To explore the connections, try starting with the yellow-highlighted cats.

There are several deadly diseases, and in an attempt to eliminate malaria, an insecticide was used to kill mosquitoes. Yet it also killed parasitic wasps and, ultimately, the animals that ate these insects (the geckos) and the animals that ate the geckos (the cats).

After using the insecticide, what happened to the cats? What about the people? Explain your reasoning to your team or peer.

Read about what happened.

Read about parachuting cats to fix the problem!

More Practice Interpreting Concept Maps?

In case you missed the link at the top of the page, for more examples to interpret concepts, see the quiz that provides feedback on incorrect responses.

Above is a concept map of the conditions of a village in Borneo prior to spraying the area with a pesticide called DDT, which initially killed the mosquitoes that were spreading malaria to humans. The pesticide killed other animals, including the cats and geckos of the village. Based on the concept map, what do you think happened as a result?

Concept Maps and Writing

John McPhee wrote about the importance of understanding the structure of the information in order to write his books and articles. Concept maps help us visualize how the components fit together, providing an invaluable writing tool. I found that assigning a concept map of the research accumulated over a week’s time significantly improved the quality of the final papers I read in Earth Systems.

0 Comments