← Radiation | Latent Heat →

Advection and Convection

Convection is the rising or sinking of fluid (a phase of matter that flows, such as liquid, gas, or plasma) with a different density than the surrounding material. In gases and nearly all liquids, density decreases as temperature increases, so if there is a density difference in the fluid, the rising convection is warmer than the surroundings. Conversely, a fluid that sinks is colder than its neighbors.

Water is our oddball, but because it is so plentiful, we need to pay attention to its oddities. As water warms above 39ºF (4ºC), it becomes less dense, and, interestingly, as it cools from 39ºF to freezing (32ºF), it becomes less dense! So there are scenarios where sinking water is warmer than its surroundings and rising water that is colder than its neighbors.

Advection is the horizontal flow of a fluid with different temperature than the surroundings. Since advection and convection involve fluids moving to and from areas, they are continually changing the local distribution of mass. If warm air rises from the surface, the surrounding air instantly moves in. Notice that this wouldn’t happen with a solid; only fluids can flow to fill in the void. In a short amount of time, convection and advection currents become connected. When this happens in nature — in the ocean or atmosphere, for example, it creates convection cells.

All materials, when heated or cooled, change density. Density differences in a fluid create movement. Less dense materials rise, and denser materials sink. Most matter becomes less dense when heated and rises. The rising fluid stops ascending when the fluids become the same density, or it hits a solid boundary. Because more material continues to flow into the region, it then advects or flows away horizontally, along the boundary, to make room.

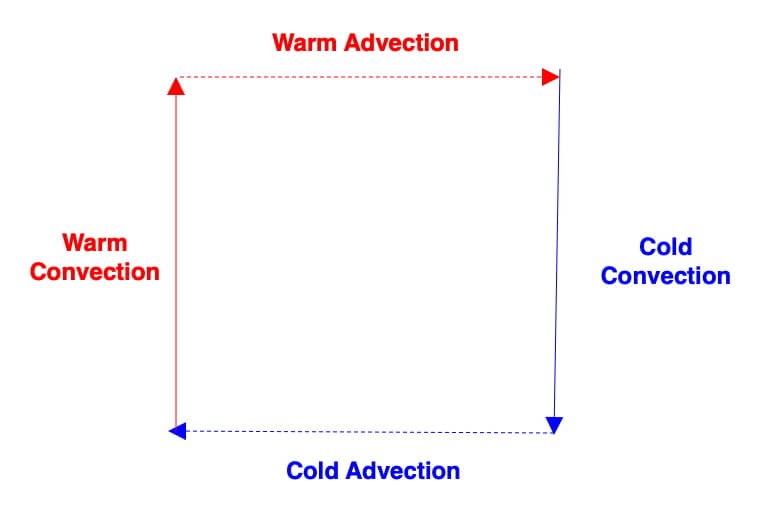

When the rising fluid is warmer than the surroundings, it is called warm convection. Sinking fluid that is colder than the surroundings is called cold convection. When boundaries stop the vertical motion, the moving air moves horizontally, so convection turns into advection.

Water is a notable exception to the rule of ‘matter always decreases in density as it warms.’ Water is densest at 4ºC (39ºF), so it becomes denser as it warms from 0ºC (32ºF). Above 4ºC, water density decreases with warming. Water can create sinking warm convection!

Hot air balloons rise into the air. One way to descend is to let it become a “cold” air balloon.

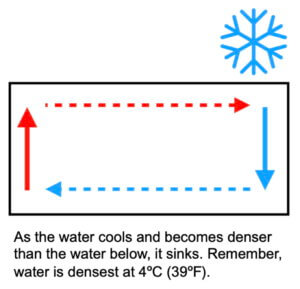

Illustration of the spatial connections between advection (dotted arrows) and convection (solid arrows) in a convection cell.

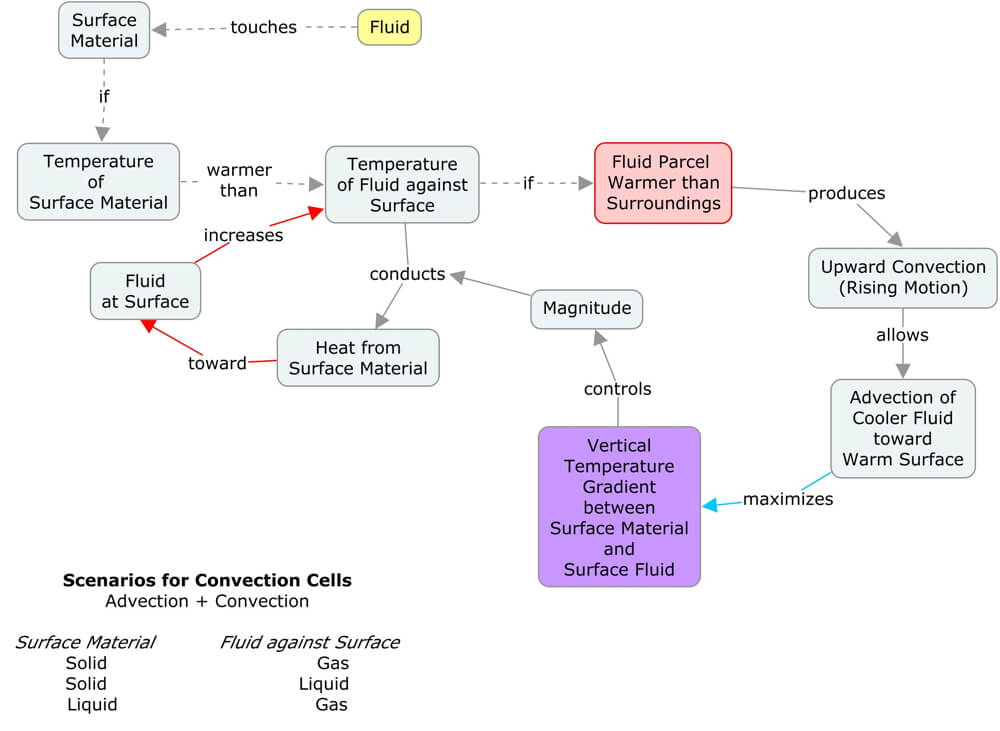

This concept map illustrates how warming surface material creates warm convection and cold advection. The colder fluid is continuously replacing the rising fluid that was warmed by conduction, which maximizes the temperature gradient between the surface material and the fluid. The magnitude of the temperature gradient controls the rate of conduction and also influences the flow of the circulation cell. Once formed, convection cells are quite efficient at distributing heat throughout the fluid to eliminate temperature differences within it.

Acknowledgments

Mattea Horne and Mort Sternheim provided invaluable suggestions during the many iterations of this concept map.

.

Additional Processes that Create Density Differences

Convection cells can also be created in water due to salinity (the density of water increases with salinity). In the atmosphere, the air becomes less dense as the concentration of water vapor increases. Since this section focuses on heat transfer, we will highlight the effects of temperature on creating advection and convection.

Experiment: Place two liquids of different densities next to each other in the same container. Watch the video. Uneven heating of the Earth’s surface creates fluids of different densities side by side. The result: moving fluids. Most of our surface wind is created this way – and the surface winds create our surface ocean currents.

Convection Cell Challenge #1

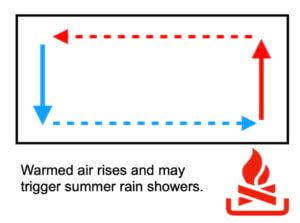

Uneven heating from below. Example: It is noontime at a parking lot on a sunny summer day. What happens to the air above the dark asphalt?

Answer to Challenge #1

Convection Cell Challenge #2

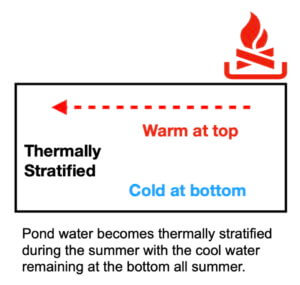

Uneven heating from above. Example: It is noontime at a pond with part of the pond in shade. What happens to the water being illuminated?

Answer to Challenge #2

Convection Cell Challenge #3

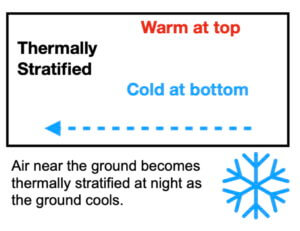

Uneven cooling from below. Example: It is 4 AM over a parking lot on a clear, cool winter night. What happens to the air above asphalt?

Answer to Challenge #3

Convection Cell Challenge #4

Uneven cooling from above. Example: It is 4 AM at a pond on a chilly night in early autumn. What happens to the pond water?

Answer to Challenge #4

Big Ideas

-

Convection is the rising or sinking of fluid (a phase of matter that flows, such as liquid, gas, or plasma) with a different density than the surrounding material.

- In gases and nearly all liquids, density decreases as temperature increases.

- Advection is the horizontal flow of a fluid with different temperature than the surroundings.

- Linked advection and convection are called convection cells.

- Convection cells move fluid of different temperatures throughout a system.

- Once formed, convection cells are quite efficient at distributing heat throughout the fluid to eliminate temperature differences within it.

- If a heated or cooled surface creates the convection cell, the moving fluid maximizes the temperature gradient that drives the cell.

← Radiation | Latent Heat →

0 Comments