← Drawing | Concept Mapping →

Research

I was well into my graduate school research exploring how sediment was transported through caves when I realized I didn’t understand what true research was – and it didn’t happen because of my work! I began exploration caving – truly going where no one had gone before in Mammoth Cave, Kentucky (the world’s longest cave).

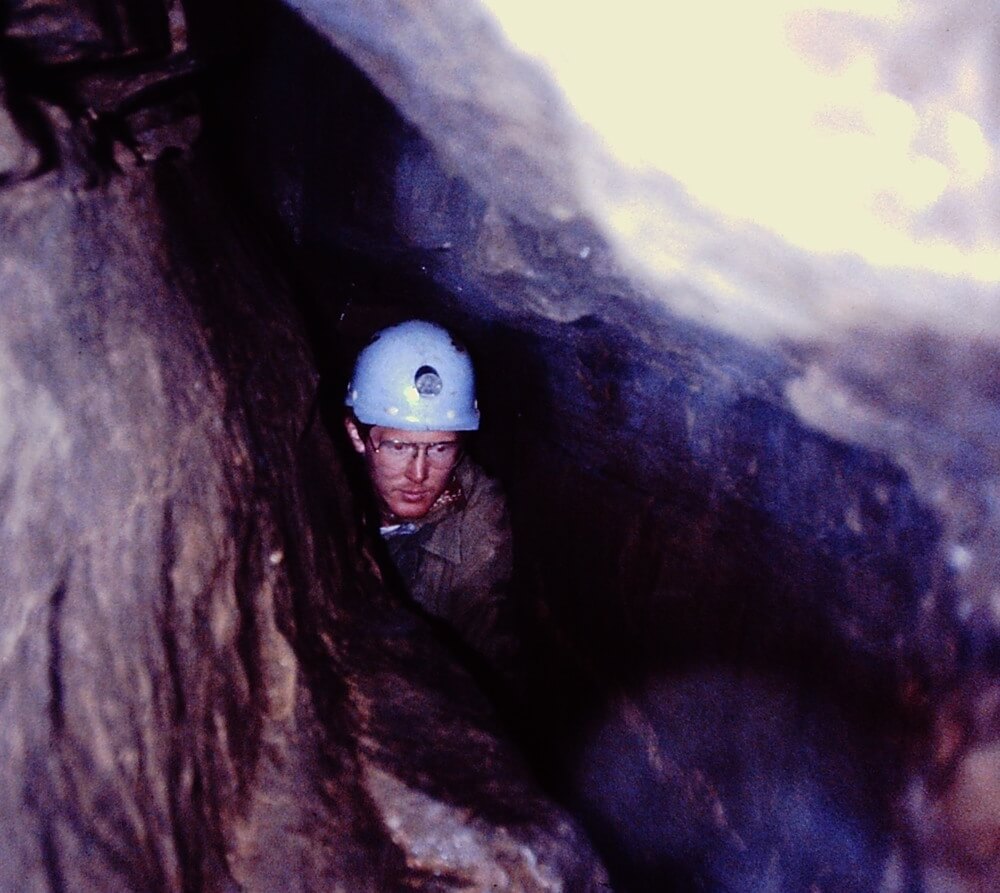

When I first tried caving I experienced a “chest compressor” – the passage was so narrow I had to exhale to make my chest smaller so I could inch forward. Our chests are our largest part of our bodies. But I didn’t hesitate since I had a map, which meant that someone else had gone there before me. So no problem!

As I was exploring in Mammoth Cave I found myself going down a passage I knew no one had ever been before, and I was in the lead. The passage was getting narrower and narrower, eventually becoming a chest compressor. I found it much harder to motivate myself to inch forward than I did when I had a map. Would the passage open up? Would I get stuck? I had no answers until I kept trying. And at that moment I realized what research was: going where absolutely no one has the answers. When I worked as a scientist, this understanding was important for me to keep trying even when the research “passage didn’t open up” – I still learned something valuable for my next attempt.

Here I am emerging from a chest compressor where I had a map, which meant others made it through safely, so I stayed relaxed. I was not as comfortable (or happy!) when I was exploring a newly discovered passage that turned into a chest compressor. The passage never opened up, and I almost got stuck trying to crawl back out of the compressor, which was at least 30 yards long.

Imagine working on something your entire career and not knowing you were correct! Only now we are proving some of Einstein’s ideas well after he died. And Alfred Wegener, who proposed a simplified form of plate tectonics (a critically important concept in Earth Systems Science) in 1912, died ridiculed by the scientific community. But we now know he was on the right path. Research scientists aren’t the only ones who live with this uncertainty. Artists, musicians, entrepreneurs, and parents all go forward without having the answers until much later (hopefully!).

Research Papers ≠ Research

Writing a research paper implies that we are involved in the act of research. Yes, we are exploring things we don’t yet know; however, if we gather the information that we believe is correct or represent “the answer,” we stop short of doing actual research. Typically we are surveying what experts in the field have compiled, so we don’t think about what isn’t known yet, and we don’t venture into the realm of knowledge that no one has the answer yet.

Note that we are not implying that research papers are not a valuable tool for learning; they are! The next time you write one, try to identify and visualize what we still don’t know about the topic yet. This is an excellent first step to prepare to do actual research.

Research Changes Our Perspective

Puzzles as a Research Experience

You may have already done this puzzle in Learning Tools’ Writing, but we can use it in a different way as a research tool. After you solved the puzzle, try making a puzzle on your own using two copies of the blank puzzle template. On the first create the solution, then create the puzzle to be solved using the second.

What questions does this open up about the puzzle? This type of research is called modeling. Creating a model of something helps us think about and explore its complex and interacting processes in new ways.

How did making a puzzle help you think about the first puzzle you solved? Some questions and ideas I had were:

- How difficult is it? Can someone solve it? How will I know prior to giving it to someone?

- Is there more than one solution? How will I know? A puzzle that only has one number will have many answers, so how many numbers are needed to create only one solution?

- Can I include numbers that aren’t along the edges? If you try placing numbers anywhere within the grid, does it change the feel of the original game?

Even if you don’t research a topic, asking research-like questions may help you gain a more insightful perspective about the concepts and connections you are exploring.

Use the link on the left to download a blank template to make your own Numbrix game. First, make your solution, then use a second copy to make your game.

Research in a Box: Mystery Boxes

Mystery boxes let you experience what it’s like to do research: explore something without any possibility of an answer. Explore a mystery box I made many years ago to determine what’s inside it. Add your ideas for additional experiments you would try in the Comments section below.

A suggestion to consider: How can modeling be used as you research what’s inside a mystery box?

Make a Mystery Box

You can make your own with simple materials: a metal box, glue or a rivet, and things to put in the box. Share them with your friends to let them try research. Better still, make several mystery boxes that have different things in them. Don’t record what is in them and put the unlabeled boxes away for at least a week. Once you don’t remember what’s inside each, then number the boxes. If you want people to understand what research is, and experience the process, you cannot know yourself.

Tip: Provide an identical metal box that is unsealed and a vast assortment of “things” that people may use to create a model of the sealed box.

Place something in a metal box, seal it with a rivet or glue, and don’t write what was inside the box. You have a mystery box to share.

If you make more than one box, number each so that people may try new experiments with the same container.

← Drawing | Concept Mapping →

0 Comments